Tanisha Singh is getting ready for work early one morning and cooking a simple curry for her lunchbox when she realizes she's out of tomatoes.

Onions are already frying in the pan. Going out to buy vegetables is not an option, as local vegetable vendors won't be open.

So Tanisha picks up her phone. On a quick-delivery app, tomatoes are available.

Eight minutes later, the doorbell rings. The tomatoes have arrived.

What might feel remarkable in some parts of the world has become commonplace in Delhi and other big Indian cities. Groceries, books, soft drinks, and even the occasional iPhone can now be delivered to people's doorsteps in minutes.

It's a convenience many don't strictly need, yet have quickly grown used to.

Unlike traditional retailers, platforms such as Blinkit, Swiggy, Instamart, and Zepto don't deliver from large supermarkets or distant warehouses. Instead, they operate out of small storage units embedded deep inside residential neighborhoods.

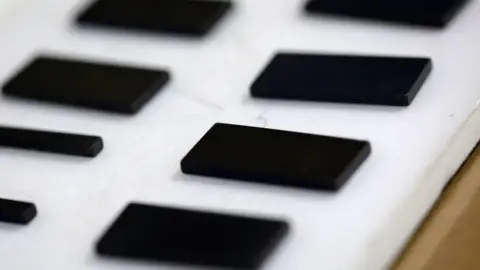

Known as 'dark stores', these facilities are typically located just a few kilometers from customers, allowing delivery riders to reach homes in minutes.

To see how this works, the BBC visited one such dark store in north-west Delhi where goods are stacked neatly on racks - with vegetables in one section, freezer units in another corner, and shelves stuffed with crisps, fizzy drinks, and even pet food.

The aisles are so narrow only the workers can weave through them, moving fast and rarely bumping into each other. The moment an order pops up on the screen, workers jump into action - picking, scanning, and packing items into the trademark brown paper bags with such speed it almost feels robotic.

Delivery riders walk up to the counter, almost in tune with the packers. Packing and pickup happen almost simultaneously - every step planned to reduce the time taken, even by seconds.

The entire process takes 16 minutes. Delivery rider Muhammad Faiyaz Alam collects a brown bag and agrees to let us join him for the ride.

On this route, Alam tries to complete around 40 deliveries a day. Depending on order volume, distance, and the incentives offered by the app, Alam earns between 900 and 1,000 rupees on a good day.

This rapid pace and reliance on smartphones and apps typify the gig economy, where many workers are classified as 'partners' and do not enjoy the benefits of traditional employment.

Despite these challenges, the convenience of quick commerce has shifted from an occasional luxury to a daily habit for urban consumers like Tanisha Singh, who acknowledges the human labor behind these quick deliveries.

Recent surveys indicate growing public awareness and support for labor protections as the government faces pressure to regulate this changing economy.

As quick commerce continues to evolve, its impact on the cities—and on the workers who keep them running—remains a critical issue to watch.